Take a quick tour to see how it works

How We Use Science

The Science Behind Kiko's Thinking Time

What are executive functions?

Executive functions are a set of cognitive skills that allow us to control our emotions and thoughts in the midst of an often-hectic world. A recent report from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard identifies three primary components of executive function: working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility.

Working memory is the ability to maintain and manipulate information for short periods of time, which is essential for executing planned sequences, whether that plan consists of dialing a phone number, carrying on a conversation, adding two numbers, or tying a shoe.

Inhibitory control is comprised of both top-down focus, or selective attention, and suppression of distractors or temptations. Selective attention is the ability to ‘tune in’ to a subset of the vast amount of sensory information that we experience in a constant stream. This is considered a top-down process because it’s directed by choice, while bottom-up distractors (external) or impulses (internal) are spontaneous. Adults depend on inhibitory control throughout daily life, for example, when driving a car with children in the backseat; children acquire it by learning social rules such as waiting to be called upon if they know an answer, or ignoring a sibling’s teasing.

Cognitive flexibility is called into play when a change in top-down strategy is warranted. This may be a procedural shift, such as realizing a math problem calls for multiplication rather than addition, or a situational strategy shift, such as knowing and following different behavioral guidelines inside school versus on the playground. Successful acquisition of this skill allows adults to adapt to different social conventions in different environments, and to adjust a work or task list based on an updated deadline.

Describing these cognitive skills independently obscures the reality that in most daily tasks, all are engaged simultaneously! However, research has shown that each of these skills is independent, and can be improved with training. We’ll share this research in future posts to explain why Kiko's Thinking Time is such an important tool for developing children’s minds.

Harvard Working PapersWhat is reasoning?

Over the years, researchers have investigated many different types of reasoning (e.g., fluid reasoning, analogical reasoning, relational reasoning, etc.), but a good general definition is the ability to integrate sets of information in order to solve novel problems. As you can guess, reasoning skills can be applied to almost any new challenge! Whenever we learn a new skill, we relate it to something we already know; when we come up against a new problem, we look for clues either from past knowledge or from the problem context to help us figure it out. Because schoolchildren are learning almost all of the time – whether it’s in school or out – they are constantly using their reasoning abilities.

In this video, Professor Silvia Bunge of the University of California at Berkeley describes reasoning as being a higher-level cognitive skill that relies on many lower-level cognitive skills, such as speed of mental processing, working memory, and cognitive control. In this characterization of reasoning, it is intricately intertwined with the executive function skills we want to develop with Kiko's Thinking Time, which is why you’ll see reasoning games alongside other executive function skills in the app.

Early childhood is the prime opportunity for executive function development

Many studies have shown that aspects of executive function can be improved with targeted training throughout the lifespan, but the window between ages 3 and 6 is the period of most rapid development. Sandra Weintraub and a large team of collaborators affiliated with the National Institutes of Health tested people from ages 3 to 85 years old, and found a fourfold increase in executive function between the ages of 3 and 6. They found a further doubling between the ages of 6 and 24, after which scores gradually decreased.

However, executive function development is not guaranteed during preschool. Children acquire these skills by interacting with rich learning environments and responsive caregivers who help them practice these skills. Liliana Lengua, Elizabeth Honorado and Nicole Bush at the University of Washington assessed 80 preschoolers’ cognitive and emotional executive functions as well as their home environments. They found that differences in home environments and parental warmth, responsiveness, encouragement, and limit-setting accounted for differences in children’s social and cognitive control. This finding underscores the susceptibility – and opportunity – for children’s executive function development during the preschool years.

PubMed 23479546PMC 3115727

Executive functions are essential for school readiness

Eugene Lewit and Linda Baker of the Center for the Future of Children reported that most parents and teachers agree: verbal communication skills and a positive, curious attitude are very important components of school readiness. However, while parents think that learning letters and numbers before kindergarten is also important, kindergarten teachers are much more concerned about their students’ ability to follow directions, sensitivity to others’ feelings, and self-regulation so they do not disrupt the class. If a student is not able to do these things, it doesn’t matter whether they already know their numbers and letters or not – it will be very difficult to teach them anything! These skills that teachers emphasize fall under the category of executive functions, because they all require cognitive and emotional self-control.

Amanda Morris and a network of researchers from Oklahoma State University, Pittsburg State University and University of New Orleans corroborated the teachers’ beliefs in a study of students’ executive functions at the beginning and end of kindergarten. They found that kindergartners’ self-control at the beginning of the year was the strongest predictor of their reading and math skills at the end of the year. Also important to academic achievement were a child’s behavior and peer relations, which are known to be related to executive functions as well.

This raises important questions for parents of preschoolers about what will truly help their children succeed in school!

PMC 3806504Improved executive functions increase academic achievement

Prior posts discussed research showing that children with better executive functions and reasoning skills were better-prepared for school behaviorally and academically. But what to do about children with lower executive function skills? Excitingly, new research suggests that training on executive function and reasoning skills leads to academic improvements!

Andrea Goldin and a team of researchers at universities across Argentina provided computerized training on executive functions to first graders. During 7 hours over 10 weeks the children played three games that exercised their working memory, inhibitory control, and reasoning, and a control group played similar but less challenging games. Both groups performed equally well at post-test on the reasoning measure, but the trained group performed better than the control group on inhibitory control and working memory.

Furthermore, the researchers tested whether the training had any effect on math and reading grades. The students who attended school consistently improved on math and reading, regardless of which training group they were in, but interestingly, the story was different for the students who had attendance issues. The ones in the trained group improved almost as much as the students who were at school all the time, and much better than the students in the control group who didn’t attend regularly. This suggests that the training helped these students catch up in academic skills as well as improving in executive function skills.

PNAS-2014-Goldin-1320217111Our Development Process

Our Development Process

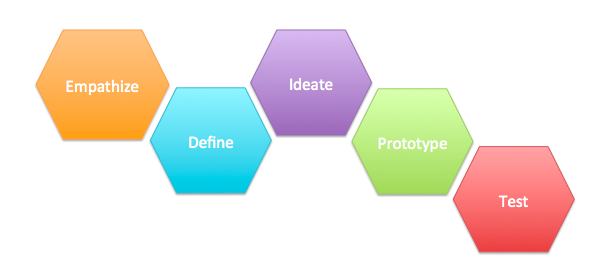

Here’s a sneak peek into our science-based development process, closely modeled on the Design Thinking Process pioneered by Stanford University’s d.school:

- Empathize. We start by putting ourselves in the shoes of a young learner, somewhere between the ages of 3 and 7. Through the process of observation and empathy, we try to understand: What triggers their curiosity? What keeps them engaged? What makes them laugh? What motivates them to try again? What challenges them? What frustrates them? We distill this into an ever-evolving child-centric design framework that anchors everything we do.

- Define. This is an important one for us. Each activity we design has a skill-building goal that’s defined at the outset. Often, it’s a specific learning goal within a cognitive skill area informed by scientific research. For example, in the category of spatial skills, we worked with researchers to define one goal as exercising mental rotation of objects and another as maintaining a flexible representation of spatial relations between objects that move (Uttal et al, 2012). The goal forms the basis for the design.

- Ideate. Now comes the fun and magical part. What are the possible ways to achieve the learning goal? What about ice creams? Pets? Teddy bears? A donut shop? What does the progression curve look like? What vectors do we play with to make things more challenging over time?

- Prototype. Once the concept is sketched out, it’s time to prototype. While we started out with paper prototypes early in the company’s history, we realized that the fidelity of paper testing didn’t get us very far, so we now go straight to digital prototypes. Art is created, the game’s basic structure is programmed and we start playing.

- Test. Testing takes many forms. Informal playtesting happens all the time on our team and our friends and family. We also work with our Scientific Advisory Board to refine our prototypes. More formal usability sessions with children-and-parent pairs and teachers are conducted through our research partner, West Ed. The final test? When the game goes live and we see how many times it’s played and how quickly children level up in the game.

Efficacy Testing on Kiko’s Thinking Time

The design of the activities in Kiko’s Thinking Time are informed by scientific research and are tasks that have shown promise in lab studies. Through a generous grant from the US Department of Education, we are excited to have an independently-led study on the impact of using Kiko’s Thinking Time on Pre-K and Kindergarten students soon.

- Stage One of the study will measure progress in cognitive skills using embedded standardized assessments in the app

- Stage Two of the study will be a randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 200 students with pre- and post- evaluative measures in executive function and early academic skills

Current Research

Kiko Labs is proud to be a 2014 recipient of an SBIR grant from the Department of Education's Institute of Educational Sciences, as well as a 2015 recipient of a Phase II grant.

Throughout June to December of 2014, our team was able to undertake a research and development effort through the funding from this grant. Our main charter was to expand the content of our original app and conduct usability and feasibility testing within authentic education settings. The research portion of the initiative was conducted in partnership with West Ed, a leading not-for-profit education research firm specialized in evaluations.

Our team took an iterative approach to research and development. We started first with teacher focus groups, focusing on Pre-K and Kindergarten teachers, and got their opinions about executive functions and cognitive skill development in an early learning setting. All agreed that these skills were extremely important for academic success and that whatever scaffolding they did was embedded in classroom practice, with little to no explicit fostering. Further, there did not seem to be tools that could be used to help with this instruction.

Next, we developed prototypes of the games which had been based off research studies and vetted by our scientific advisory board. The prototypes went through usability testing, where we had one-on-one sessions with teachers and children (with their parents observing) playing with the app. We learned what worked and what did not work in the hands of four and five-year old children. We took that feedback and refined our prototype for the next stage of research.

In the final study, we conducted a feasibility study in two classrooms (one Pre-K and one Kindergarten) where children were exposed to the app over a longer period of time within a classroom setting. Our main questions here was whether teachers were able to integrate the app into their classroom routines and whether children would stay engaged with the app with minimal supervision. We were very encouraged to learn that children were extremely engaged with the app, with average play sessions lasting 12 minutes. Over a one-week period, the Kindergarten class had on average progressed 4 levels across all the games. The teachers were very impressed with the app and all said they would use the app when it became available.

With these encouraging results, we applied for and received a Phase II grant. The Phase II grant will allow us to build on the results of these studies, further expand our product and conduct a larger pilot study with pre- and post- evaluative measures. The goal is to determine how Kiko's Thinking Time strengthens executive functions and reasoning, and how this impacts academic outcomes in early learners.

We're just getting started!